Death of the Saturday Job

Should teenagers combine work and studies to get ready for the world of work?

Paul Carter

6/2/20254 min read

Spring 1996, not long until my GCSEs. I am in Waitrose, listening to the Oasis album Definitely Maybe on my Walkman, getting ready for my interview. Like my older brother and sister before me, I wanted a weekend job. I needed to pay my way through sixth-form college as toasted cheese baguettes, pink salmon shirts and Thursday nights at Cinderella’s cost money.

Working and studying was a rite of passage when I was growing up with wages around £4 per hour and double on a Sunday. Teenagers earning and learning up and down the high street, retail parks and service economy.

The labour market has changed since my days as a cashier and trolley pusher with news articles, government reports and think-tanks announcing the death of the Saturday job and the impact this has on the education-to-work transition.

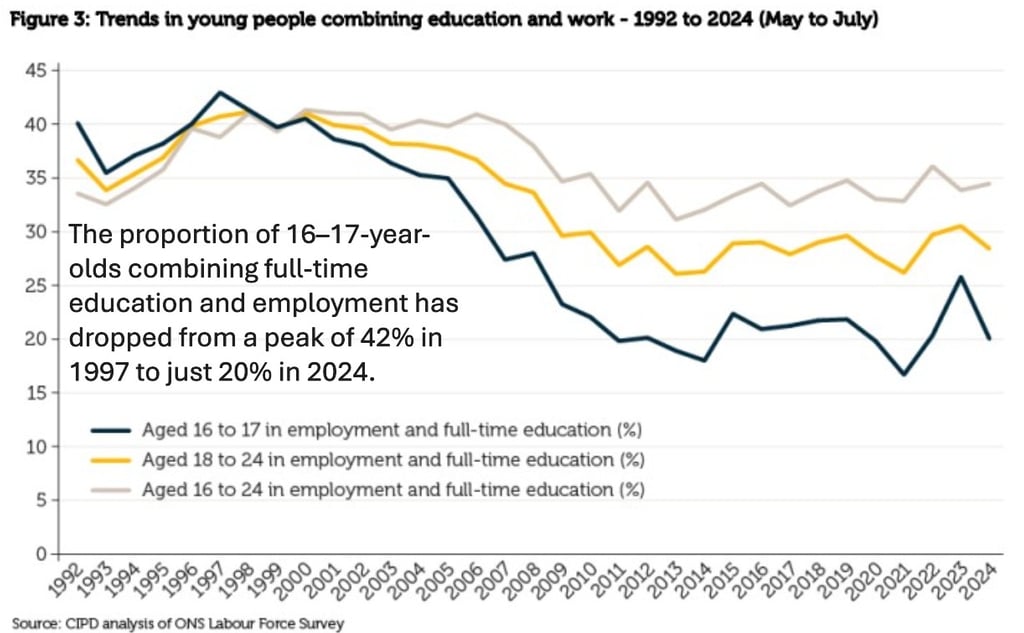

The employment rate for 16-17 year olds has halved over the past two decades, from 48% in the late 1990s to 25% in the 2010s. ‘The proportion of employed 16- and 17-year-olds who are also in full-time education is at its lowest level in a decade, at just over one in five between July and September this year,’ reported the Daily Telegraph in December 2024.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to concerned parents reading that headline, wondering if their teenage children could get a job to shave a few hundred pounds off the £260,000 average cost of raising a child to age 18 in the UK.

Why has this happened?

In 2014 the UK Commission for Employment and Skills attributed the death of the Saturday job to young people prioritising studying, a changing labour market affecting the opportunities for part-time jobs, and institutional difficulties with incorporating work into study timetables. A decade later those factors remain, along with national insurance implications, safeguarding requirements and the difficulties with zero-hours contracts.

I still have a recurring dream where I go back to school as an adult but have lost my timetable and can’t find the classroom. I also find myself back on the till in Waitrose unable to remember the codes for cinnamon swirls. When I secured my weekend job, my dad lost his permanent job. College was so much better than school but teenage years are tough and my weekend job gave me money, friends and stability.

This Bartleby article in the Economist The Early Lives of Bosses references research on how early experiences such as recessions, family power dynamics and exposure to risk and trauma can influence the way people behave at work decades later.

If teenagers aren’t working in their formative years how will they escape their teenage bubble and develop the workplace maturity and skills that employers need? I would have wondered why my employer was asking me that question when I was younger as I thought adults had all the answers.

What are teenagers missing?

The UK population is ageing and births are well below the replacement rate, meaning the shelves are not being stacked with enough 16-18 year olds to feed the talent pipeline and meet business needs. I regret not working while studying at university as it was incredibly difficult to find a job after I graduated.

While I proselytise about weekend jobs, the rallying call to get adolescents ready for the world of work may go unheard if they do not understand why it matters. The halcyonic times of weekend and summer jobs fill column inches and endless streams of comments of memories of yesteryear.

‘By the way, nostalgia is only useful when you’re selling something,’ says the chief executive of Pierpoint investment bank in the TV drama Industry as it struggles to stay solvent after a bad investment in sustainability. The young bankers wanted to change the world but discover it’s not that easy.

The death of the high street, living through the pandemic where deaths and infections were line graphs that filled their TV screens, teenagers might not want to spend their weekends saying, ‘Next, please!’ if they can develop life and work skills in a different way to their parents and still get a job because of the scarcity of talent and skills.

Maybe. Depends how talented you are and what the competition is for jobs you want. The young people combining work and study with extracurricular activities to develop leadership and interpersonal skills could have the resilience, professionalism and behaviours that employers say their generation is lacking.

The ‘huge expansion of the higher education system over the past few decades, means the youth labour market is increasingly well educated,’ reported the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

The trend of prioritising study over weekend jobs may be good for higher education, but the CIPD found this increase has not been accompanied by a corresponding rise in high-skilled jobs. As a result, many graduates find themselves in roles traditionally occupied by non-graduates.

You never stop learning

As weekend jobs are to fund teenage lifestyles, they have time-limited benefits for careers. It’s about life experience and interacting with the world and society. When I see teenage or student workers do their jobs with professionalism and deal with difficult customers, I see them as my equals. When they are grumpy or reluctant, I can empathise and see the same traits in adults.

I predict AI will replace traditional entry-level office jobs and frontline and public-facing entry-level roles will require a higher standard of interpersonal communication.

Work experience and career paths will matter. I support traineeship and pre-apprenticeship programmes to help young people move into employment. The Skills Imperative 2035 has found that many of the skills young people currently lack are forecast to increase in importance.

Employers should engage with emerging talent to help them develop the transferable skills such as critical thinking, collaboration and problem-solving to continue our great work.

Inspiration

What we talk about when we are working and living

© 2025. All rights reserved.